A Photographer’s World: The Art of Randeep Maddoke

Introductory text by Jasdeep Singh

Photographic captions by Randeep Maddoke

“The first light that entered our one room home was from a roshandaan near its entrance. It got projected on a wall opposite my bed. That was my first television and shadows my first show. I would lie there watching it, entertained.” Randeep recounts his childhood experiences of growing up in a Dalit landless household in Maddoke, a village in Moga district of southern Punjab.

These experiences and this eye to spot beauty in patterns and shadows stayed with him thereafter. It became more piercing and led him to become a professional photographer. As a child, he studied in a government-run school, where he grew fond of books. The first book that struck him was Roos Da Itihaas (A History of Russia), a well-designed book with paintings printed on a fine paper. He was enamoured of it.

Randeep then started to draw. He sent his works to the annual festival organized by the activist groups of the region. It won him awards and praise. He later joined an activist group and began working with them. He bicycled through villages in his district and the neighbouring regions, organizing meetings on labour and farmers’ rights.

The family could not support his studies after Class 12. So he took up odd jobs. He did agricultural labour, daily wage labour in town, and painted houses; and he continued organizing labourers from his community. He began a theatre group in his village. Yet his pursuit for beauty and social justice remained unfulfilled.

Then, he came across a newspaper advertisement about admission to the Government College of Art, Chandigarh. At the age of thirty, after eight years of labour and activism, he sold the small plot of land he had inherited, and began a BFA in the big city. He studied painting and chose photography as an optional subject. He borrowed an old camera from the garage of one of his activist friends. By the time he graduated, he had realized that he was interested in photography, for the kind of things he wanted to express.

It has been ten years since. His first photographic project was Mirage: A Study of Shadows. His recent project on the paradox of the prosperity of the green revolution took him to Dalit neighborhoods of southern Punjab. He is documenting the socio-economic aspects of landless labourers in the regions, where there have been reports of farmer suicides. The focus of media and activist groups has been on landowners but effects of agricultural crisis in the cotton belt on lives of those who depend on land are under-documented. He has also followed the right to common land movement by Dalits under the aegis of Zameen Prapati Sangarsh Committee. He is now expanding his canvas and his next work will seek to tell the story of the landless laborers with the moving image. The documentary project titled, ‘Landless’, is due to be released this year.

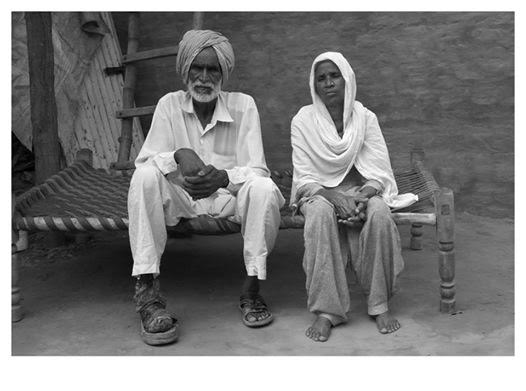

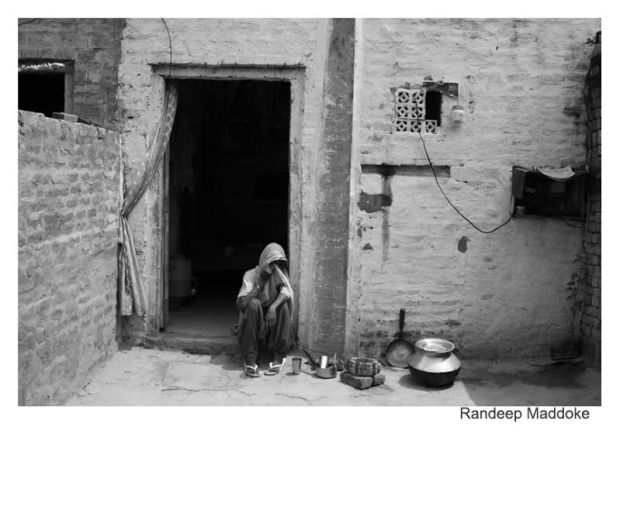

The accompanying photo essay is from this very project. Two girls are sitting with their back to the camera against a vast expanse of wheat crop; across the green frontier, a concrete structure looms large. The camera captures their fear of the surroundings. The colorful bales of chaff in a harvested field evoke a celebratory sense, but when you read the story behind those colors, this sense dissolves in despair. Labourers cleaning the grain in the market throw a pattern of sickle in the air. The story clears the air about issues in the hammer and sickle politics. A young girl is collecting cotton wool and another child is ‘separating grain from chaff’ and Randeep underlines, ‘it is labour, it is obligatory / the school is faraway/ for food, it is necessary / it is labour, it is obligatory’. The last two photographs are of families of landless labourers ‘left behind’ after their sole earning hand decided to end their life stifled by the endemic poverty and indebtedness.

Randeep suggests that the market drives the contemporary visual language of photography. The individualistic, commoditized image is being propelled to the forefront. He is looking to stay away from the contemporary style of image-making and wants to try out new possibilities.

– Jasdeep Singh

Fearful of the surroundings

I took this photograph in my college days, when I was a BFA final year student. There was a competition ‘Chandigarh in April’ organized by the Chandigarh Tourism Department. I took many photographs from different angles and got the first prize.

While I was taking this photograph, the Dalit girls became conscious of me, stopped their wheat-harvesting and turned their faces to the other side, towards the state secretariat. At that point, I got the image I was looking for.

On one side, these Dalit girls are working in someone else’s wheat fields and, on the other side, there is state complex (designed by Le Corbusier, a World Heritage building) of the government run by the upper castes. Their status is similar on both sides.

***

Our share is just chaff

Most Dalits are landless. They do not have their own land and that is why they have to work as agricultural laborers. Every season they harvest hectares of wheat fields and, in return, they earn modest wheat and chaff. The wheat does not last long as the quantity is much less than their annual needs; so they have to borrow wheat or have to take loans to buy wheat.

In this image, there are many colourful bales of chaff. These bales are in the women’s stoles because they do not have enough sailcloth.

***

Our sickle is always here but where is your hammer?

This picture is from the grain market of village Ghudha, in district Bathinda, Punjab. Dalit labourers are cleaning the heaps of wheat grain. The pattern of sickle is formed in the process and the Dalits are under its shadow. They are one part of the hammer-sickle class, yet they are neither proletariat nor Dalit.

The condition they are in is not because of their class status but due to their caste status. Indian communists believe that there is no caste, only class; but in reality, every aspect of society, communists included, is caste-based.

The picture calls out the same question: are we Dalit or the Proletariat?

***

The price of cotton

The ten-year-old girl in the picture has never been to school. From the time she has learnt how to walk, she has been picking cotton wool and wheat bales from somebody else’s field. After all these efforts, she has not earned enough to afford the tiniest bit of happiness for herself. Similarly, so many people from their childhood to old age toil in another’s fields and yet, have not been able to buy some land or some solace for themselves.

***

Separating the grain from chaff

Majdoori hai, majboori hai

School ton iss lai doori hai

Khatir pet, jaroori hai

Majboori hai

Majdoori hai

it is labour, it is obligatory

the school is faraway

for food, it is necessary

it is labour, it is obligatory

***

Left behind – 1

In a time of crisis, a civilized society looks to safeguard the most vulnerable people because every crisis affects them more. However, in the case of the agricultural crisis in Punjab, it has been the other way around. Everybody talks about the farmers first, but in this crisis, it is the agricultural labourers who have been hit the hardest. They have been almost pushed out of the agricultural subsistence economy. Due to absence of alternative employment, they are pushed into a situation even more precarious. The number of landless labourers committing suicides has been equal to that of farmers. The numbers of landless women who have committed suicides is three percent more than the women owning land, which is worrisome.

Farmers are pushed to suicide due to debt taken from banks, commission agents, and co- operative societies. But the landless labourers do not get money from these entities because the labourer is unable to produce a guarantee to borrow. So the reasons behind his suicide are extreme poverty, disgrace, unemployment, and despair. A small number of them commit suicide due to debt, which they source not from banks, commission agents or co-operative societies but from well-to-do farmers. Someone committing suicide due to malnutrition is in a worse situation than someone committing it due to debt. His situation should be dealt with on an urgent basis. After a labourer commits suicide, there is no relative or organization, which can support the surviving family. We can easily imagine the situation after his death.

***

Left behind – 2

Karamjit Kaur, aged 30, village Kotra Kaura (Rampura, district Bathinda). Her husband committed suicide fifteen days before this photo was taken. He was mentally disturbed because of his debt of eighty thousand rupees. She has two children: a girl aged 3 and a boy aged 5. Her in-laws are not well. She does not have any means to live and take care of her children and in-laws.

Bios:

Jasdeep Singh is a translator, blogger, and software engineer based in Chandigarh. He curates a blog on translated Punjabi poetry. He has worked as an additional dialogue writer and translator for the critically acclaimed Punjabi films, Annhe Ghore Da Daan and Chauthi Koot.

Randeep Maddoke is a photographer and filmmaker from Punjab. He has documented everyday experiences of Dalits in Punjab, Haryana, and Tamil Nadu to study the operation of caste, power, and hegemony. In Nepal, he has documented the armed struggle of the rebels, the majority of whom are from the Dalit castes.

***

For more stories, read Café Dissensus Everyday, the blog of Café Dissensus Magazine.