An Ambivalent Attraction: Some Thoughts on the Hitler Phenomenon in India

By Ryan Perks

In India today, Adolf Hitler’s likeness circulates with a sort of nonchalance unknown in the West since the 1930s. There are Hitler ice cream cones, Hitler hair products, Hitler cigarettes, Hitler cologne. There are menswear stores, pool halls, and restaurants. There are films and television shows with Hitler in the title, often used as a synonym for their loveable, if authoritarian, main characters. To be sure, some, like the controversial 2011 film, Dear Friend Hitler, about Hitler and Gandhi’s wartime correspondence, try to tackle the Nazi legacy a little more directly. But many others, like the widely popular television series, Hitler Didi, about a young woman in Delhi burdened with the care of her family, have nothing to do with German history.

Television Series, ‘Hitler Didi’

The ambivalence toward Hitler and his legacy is also demonstrated by the popularity of his 1925 prison memoir, Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”). Banned outright in some countries, it is a bestseller on Flipkart and Amazon, two of India’s largest internet retailers. Jaico, the book’s most successful Indian publisher, has sold over 100,000 copies in the last decade. About five years ago, in Delhi, the company reported selling 10,000 copies in one six-month period alone.

Hitler Ice Cream

The book is sold by at least a dozen other publishers as well, and in most major Indian cities, it can be bought in countless less expensive pirated editions. Electronic copies, downloaded on iTunes and Amazon Kindle, are consistently among the country’s highest-selling ebooks; free PDF downloads are, for obvious reasons, even more popular, though their numbers are hard to track. Mein Kampf can be read in one of its original English translations (German is not widely spoken in South Asia), or in several of India’s many regional languages. It can be purchased at a place like Bahrison’s, one of Delhi’s most upscale English-language bookstores, or in Daryaganj, in the city’s medieval quarter, where every Sunday shoppers converge on one of the country’s oldest and most colorful open-air book markets.

This tends to surprise Western visitors. For some, Mein Kampf’s seemingly unhindered presence in Indian book culture is made more surreal by the fact that other books have been banished from the public realm. At a red light in Mumbai, or waiting for a train in Lucknow, you can buy a copy of Hitler’s book, condemned in many countries as anti-Semitic hate speech, for less than $3, but just try to find yourself a copy of, say, Salman Rushdie’s 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses, in a Delhi bookstore.

Even still, the so-called Hitler phenomenon isn’t quite as strange or unprecedented as it may initially seem. Early Hindu nationalists like K. B. Hedgewar, the founder of the right-wing Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and M. S. Golwalkar and B. S. Moonje, two of the group’s earliest and most influential members, were not shy about their admiration for European fascists like Hitler and Mussolini in the 1920s and ’30s (a topic about which the Italian historian Marzia Casolari has written in great detail).

During the Second World War, Subhas Chandra Bose, leader of the anti-colonial Indian National Army and a former president of the Indian National Congress, famously spent two years in Germany trying (unsuccessfully) to enlist Nazi leaders in the anti-British struggle. Knowledge of this episode has helped perpetuate the myth that Hitler, the “enemy of my enemy,” as it were, was integral to the overthrow of the Raj. However, the historical ties between European fascists and certain members of the Indian elite do little to explain why ordinary Indians continue to display a fascination with Hitler.

Hitler Cross

Hitler Indian Store, Ahmadabad

There is evidently some anxiety about this in the West. In the last decade, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Huffington Post, the Globe and Mail, the Guardian, Der Speigel, the Jerusalem Post, the BBC, among many others, have devoted column space to Indian youths’ fascination with Hitler. Almost all of these reports present variations on a standard theme: young Indians have embraced Hitler in alarming numbers, and this trend reflects, if not an outright embrace of Nazi ideology, then at least a dangerous indifference to Hitler’s message of national purity and racial domination.

While I would not want to be complacent about this issue, I think there is a less alarmist way to look at Hitler’s ubiquity on the Indian Subcontinent. Namely, I think the fascination with Hitler shows that historical meaning itself is increasingly subject to globalization. In the twenty-first century, in the age of the internet, of international hyper-capitalism, historical phenomena – in this case Hitler and his legacy – are increasingly likely to be untethered from the context in which they were produced, only to be reimagined, repackaged, and consumed anew in surprising, perhaps even troubling, ways. This point might be best illustrated by a brief story.

A couple of years ago while I was in India for several weeks I was invited to visit a university outside of Delhi. I had been meeting with a professor at the school, and one evening he suggested we take a stroll around the campus. It was just before Diwali, and the grounds were relatively deserted, but eventually we came across a group of students sitting together in the central courtyard. My host, knowing of my interest in the subject, insisted we ask them about Hitler.

Initially, the students were at pains to stress that they were business students, not historians. But as the professor rightly pointed out, “irrespective of the academic discipline they belong to, irrespective of the region they come from, Ryan here just wants to get a sense of what the Indian youth think about Hitler.”

In their answers, the students made it clear that they abhorred all that Hitler stood for. True, there was a great deal of ambiguity in their statements, if not outright ignorance of the historical record (one girl, for instance, told me that Hitler’s true crime was coming to India and mistreating the local population). But in the end they were emphatic: they did not agree with Hitler’s methods or ideas, and they were certainly not anti-Semites or Nazi sympathizers.

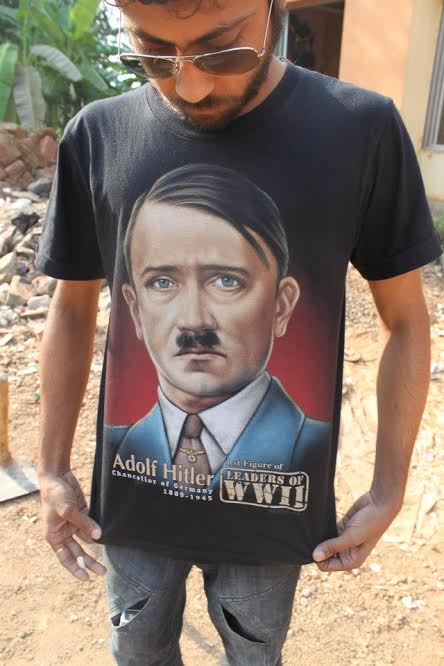

Just then my host stepped in and asked a hypothetical question: “Suppose that Ryan decided to distribute t-shirts with the Nazi swastika here on the campus for free: would you like to grab one for yourself?” They had just finished telling me what they thought of Hitler – that they strongly disapproved of him because he was guilty of “not listening to others,” of being “a dominator,” and that he was “against democracy” – and yet when asked that if they would wear the swastika-emblazoned t-shirts that I was hypothetically giving away at their school, they answered “Yeah, obviously!” When I asked why, they replied in unanimous chorus: “because they’re cool!

Swastika T-shirt

Hitler Indian T-shirt

An analogous example would be the Che Guevara t-shirts so popular among young people in the West, or the cheap reproductions of Andy Warhol’s famous silkscreen portrait of Mao Zedong one might find in any student dorm. Both depict controversial, even widely reviled historical figures, but both are consumed in ways that do not reckon with the specific historical context from which they come.

We know, similarly, that a large number of Mein Kampf’s readers are not historians or policy experts, but students, many of whom tend to view Hitler’s memoir as a sort of aspirational self-help text. As Sohin Lakhani, owner of Embassy Books, told the Daily Telegraph in 2009, these students see Mein Kampf “as a kind of success story where one man can have a vision, work out a plan on how to implement it and then successfully complete it.” This fact is often left out of Western media reports on the subject.

It is nonetheless necessary to end on a note of caution. It would be wrong, I think, to view Indians’ fascination with Hitler as a direct indication of their embrace of Nazi or fascist ideals – indeed I’ve tried in this essay to point to some of the ways in which this fascination might indicate a more ambivalent fascination.

Hitler Clothing Shop

While Suman Gupta has argued that India isn’t “singularly vulnerable” to the charms of a reactionary political program, neither, he points out, “is it especially immune.” In other words, the unfettered circulation of Hitler’s image, indicative as it may be of a more or less innocent fascination with decontextualized objects and symbols, must be shown for what it is, or rather what it could potentially become. This does not mean that scholars should take less interest in the Hitler phenomenon in India; rather, they should take more. It is, after all, up to intellectuals and academics – writers, filmmakers, historians, political scientists – to restore Hitler to his proper context, and to remind modern Indians just how dark the history behind his image is.

Bio:

Ryan Perks is a freelance writer and editor. He holds a master’s degree in history from Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario.

***

For more stories, read Café Dissensus Everyday, the blog of Café Dissensus Magazine.

Err and why should we shreik in horror at the mere mention of the word Hitler? He was supportive of Indian national movement, if only to reduce the British fighting power. World war 2 might even be more responsible than Gandhi in getting us freedom. And why is Hitler so special? There’s an armed Maoist movement. I don’t see you troubled by this. At least we’re not fawning over him and still see him negatively, unlike how the West sees Churchill. He was responsible for millions of death during Bengal famine. When told of this he replied why is Gandhi not dead then? True psychopath. And how does the West sees him?